Spectral sequences are among one of the most useful tools for topology, geometry and algebra. However, they have the reputation for being difficult to grasp.

Roughly, they approximate the homology of some chain complex, by breaking it up into many little pieces. A nice example of this arises in topology, where we can filter such a complex:

Recall that, given a space , we may form the cohomology ring

which is graded, by the cup product:

which, up to degrees, is commutative:

.

Our goal is to compute this cohomology ring. For simplicity, let be a CW cell complex and

be a CW pair. Then this induces a long exact sequence in cohomology:

.

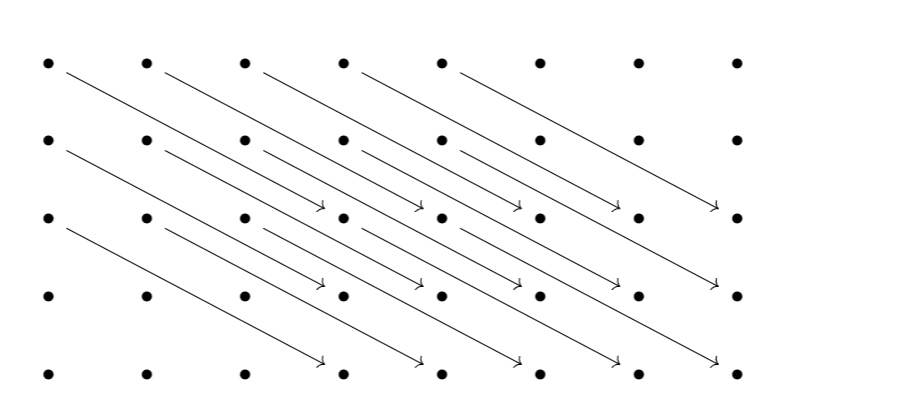

This is good; we can use this to help us with our computations- but why stop here? We now introduce a filtration to the mix:

which, similarly, induces two long exact sequences in cohomology. Hopefully, one can see where we are going: introducing a filtration of the form

will give us many long exact sequences in cohomology which will help to approximate the cohomology of . The method for storing all of this data is called a spectral sequence.

We say that a collection

is a spectral sequence if:

- For all

is an abelian group.

- The differentials

satisfy

- The homology of the

th page is the

th page. That is:

We say that the spectral sequence collapses at the th page if:

.

Furthermore, we say that the spectral sequence converges to a graded object if we can sum along the diagonals to get:

, modulo certain extension problems.

When this happens, we write .

I shall finish this blog post by talking about exact couples how to construct the Bockstein spectral sequence, using exact couples, as an example.

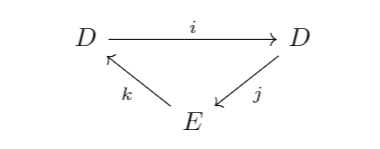

We say that is an exact couple (where

and

are modules) if the following diagram is exact at each vertex:

But now things get interesting. We can set as being

. Note that

satisfies

since:

by the exactness of the diagram. So it makes sense to introduce the notion of the derived couple.

Given an exact couple , we define the derived couple

as follows:

The derived couple is exact.

Therefore, we can iterate this process to get infinitely many exact couples :

If we let , then

is an example of a spectral sequence. We now move onto the Bockstein spectral sequence construction:

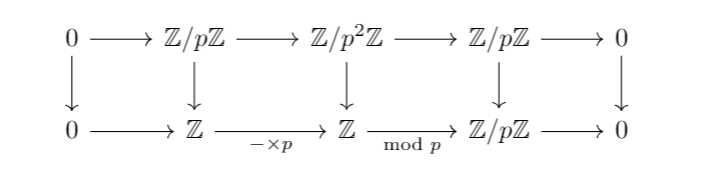

Recall that we have a short exact sequence of groups:

which yields a short exact sequence of chain complexes:

and hence a long exact sequence in homology whose boundary map is called the mod

Bockstein.

The following commutative diagram of short exact sequences shows that factors as a composition

.

Therefore, we have an exact couple

where the maps are induced by the short exact sequence . The differential

is given by

and

is called the

th Bockstein homomorphism. It turns out that:

If has no infinitely

-divisible elements then:

in the mod Bockstein spectral sequence.

Next time, we shall discuss some applications of the Bockstein spectral sequence.

Thank you for reading!