Because of my upcoming video about higher category theory, I thought I would make this short blog post introducing categories and some related ideas about them. Therefore, this will be a pretty long blog post, with lots of advanced examples sprinkled in (they aren’t necessary for actually understanding the category theory itself, but they are really cool examples of how we can translate concepts from different areas of maths into category theory).

Introduction:

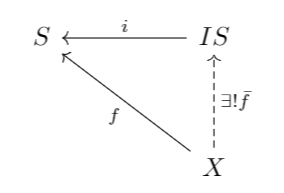

In category theory, there are certain concepts that pop up all the time. One of the most common is the “universal property”. This is a certain defining property which describes an object in a certain category

Example 1

Given a set and an element

, there is a unique map

which is given by mapping any element . This means that, given a set

, an element

has the universal property that there is a unique map

Example 2

In topology, the discrete topology on a set has the unique property that any map

is continuous. More precisely, let be the underlying set,

be the set equipped with the discrete topology, and

be any topological space. Then, given the functions:

where is arbitrary, then there is a unique continuous map

such that

commutes. Let’s unpack this a little bit more: the commutativity of the diagram means that for all

. More precisely, since

, this means that

. This is true for all topologies, you may scream, however in that case you are forgetting the requirement that

is continuous. Therefore, all this is saying is that any function

can be made continuous if you let

have the discrete topology. This is a universal property since this is only true for the discrete topology. Consider, for example, trying to replace

with the indiscrete topology. The statement would fail horribly in that case! However, the indiscrete topology does give rise to a similar universal property. It is, what is known as the dual of the discrete topology. Essentially, what this means about the universal property is that all of the arrows in the diagram above will be reversed. That is, the diagram will now look like:

with the same explanation as before, except that this time the indiscrete topology has the universal property that any map

is continuous rather than any map

being continuous which was the universal property of the discrete topology.

Categories:

Definition 1

A (small) category is a collection of objects along with the following data:

- A set

of objects

- A set

of arrows (or morphisms) between two objects

and

.

- For a triple

of objects, there is a composition law

which we denote

We may also write compositions as follows:

The composition law must be associative and unital, that is: for any and

we have it that:

and there is a morphism called the identity such that

and

.

Example 1

Consider the category Top of topological spaces, where the morphisms would be continuous maps.

Example 2

Consider the category Ab of abelian groups, or Grp of groups, where in both cases the morphisms are group homomorphisms.

Example 3

Consider the category Set of sets, where the morphisms are just functions.

Functors:

Definition 2

A (covariant) functor is a map of categories. It assigns an object

to an object

. Furthermore, it will assign a to morphism

between objects in

to another morphism

in

such that:

and

or if then

is called a contravariant functor.

Definition 3

Given a category , we say that

is the opposite category of

if:

There are of course many very interesting examples of functors:

Example 1

We have so called “forgetful functors” which drop the added structure of the underlying set. For example:

which just sends a group to the underlying set

and so on (there are many examples of such functors).

Example 2

The fundamental group is a functor

Example 3

The delooping of a group is a functor too. What the delooping of a group does is describe a group as a groupoid with one object. More precisely, given a group , the delooping of

, denoted

is a groupoid (category where all morphisms have an inverse) with one object

and morphisms

elements of , composition is multiplication in

, identity morphism is the identity element in

and the inverse morphisms are inverse elements in

. So

is a functor

Example 4

The fundamental groupoid of a space is a groupoid which assigns to a topological space

a groupoid $\Pi(X)$ which has:

points in

But how exactly does it extend to a functor? The answer is that it extends to a groupoid

by sending a space to a groupoid

and a map

to a morphism

which sends

.

Natural Transformations:

A natural transformation can be thought of as a morphism between functors.

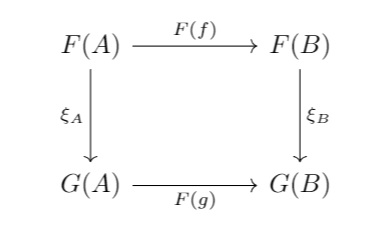

Definition 1:

A natural transformation between functors consists of a morphisms

such that:

commutes.

Definition 2

We say that is a natural isomorphism if every single

is an isomorphism for every object

. Two functors are isomorphic if there is a natural isomorphism

.

Example 1

A statement like

“A group is isomorphic to its opposite group”

can be expressed in terms of a natural isomorphism. More precisely, define the opposite of a group ,

to be the same set as

but the operation is given by

.

We can quickly move down to functors by defining

,

It is in fact a group homomorphism since

Now we can move up a level to natural transformations by saying:

The identity functor is naturally isomorphic to the functor

And so we have rephrased “A group is isomorphic to its opposite group” in terms of natural transformations.

Example 2

In algebraic topology, the Hurewicz homomorphism is also a natural transformation! This is because both

and

are functors, the Hurewicz homomorphism is natural for all and the following diagram commutes:

A Glimpse at Higher Category Theory: The 2-Category of Categories

In order to avoid paradoxes and size issues like Russel’s paradox when talking about the “category of categories”, we restrict ourselves to small categories.

Now we have a tiny glimpse at higher category theory. In the category of small categories, we have the following data:

- Objects are just small categories

- Morphisms are functors

- 2-morphisms are natural transformations

But what are -morphisms? Well, they are what they sound like: morphisms between morphisms. One of the ideas behind higher category theory is to study such “higher morphisms”. It is hard to make precise the case when we have higher morphisms between morphisms, higher morphisms between those ones and so on forever. However, that is for the talk to make precise….